By Briana Clark

On June 27, 2018, Justice Kennedy, a crucial swing vote in numerous civil rights cases, announced his retirement from the Supreme Court. Justice Kennedy’s retirement placed many people in fear that several important rights and privileges afforded to underrepresented communities will begin to be curtailed. Because the decisions of the Supreme Court—and in many cases the decision of one swing vote, often Justice Kennedy— undoubtedly and pervasively impact the livelihood and rights of millions of people, it is imperative that we recognize what is truly at stake with Justice Kennedy’s retirement.

For example, just one month ago, the Supreme Court rendered a decision, written by Justice Kennedy, in Masterpiece Cakeshop, a landmark case with many implications with respect to the rights of people targeted by discrimination—especially members of the LGBT community. The case addresses the First Amendment right to the free exercise of religion and, importantly, the ways in which the United States addresses its troubled history of discrimination on. Indeed, what may be less obvious about particular elements of this decision is that, taken out of context, the Supreme Court’s language can be read to suggest that simply stating a historical fact about the use of religion as a justification for discrimination may be considered hostile. This is especially important given the current administration’s recent misrepresentation of biblical scripture to justify forcibly ripping children from the arms of their mothers and fathers as punishment for seeking refuge from politically corrupt countries. Our society will never reckon with our history, nor will we address the ongoing harms that pervade our country, if merely stating the truth about the ways in which religion has been used, both in the past and present, to justify terrible wrongs is deemed as hostile.

In Masterpiece Cakeshop, a baker refused to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple because of his religious beliefs. The couple filed a charge with the Colorado Civil Rights Commission alleging discrimination. The Commission and Colorado Court of Appeals agreed with the couple. The Supreme Court cited statements made by the Commissioners, including comments that mentioned slavery, as well as the disparate treatment by the Colorado Commission of other cases regarding the sale of cakes to hold that the Commission was hostile to the baker’s beliefs and violated his religious rights under the First Amendment.

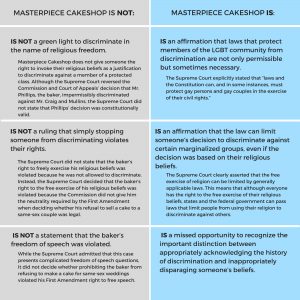

Reactions to this decision have ranged from people misinterpreting the case to argue that business owners are now authorized to discriminate due to their religious convictions, to people recognizing that the decision affirms the right of LGBT individuals to be free from discrimination. Although people on many sides of the debate have claimed Masterpiece Cakeshop as a win for their side, this piece unpacks the meaning of Masterpiece Cakeshop with a special focus on the Court’s missed opportunity to distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate acknowledgment of the history of our country as it pertains to slavery.

The major holding in Masterpiece Cakeshop was that “the Civil Rights Commission’s treatment of [Phillips’] case ha[d] some elements of a clear and impermissible hostility toward the sincere religious beliefs that motivated his objection,” which violated his First Amendment free exercise rights. One example of hostility cited by the Court was statements made by a Commissioner at a formal public hearing on July 25, 2014. Specifically the commissioner stated:

“Freedom of religion and religion has been used to justify all kinds of discrimination throughout history, whether it be slavery, whether it be the holocaust, whether it be—I mean, we—we can list hundreds of situations where freedom of religion has been used to justify discrimination. And to me it is one of the most despicable pieces of rhetoric that people can use to—to use their religion to hurt others.””

At the outset, it is critical to recognize the importance, as the Court notes, of access to “a neutral decision maker who will give full and fair consideration” to a person who is raising his or her arguments before a decision-making body. While I may not have reached the same conclusion, the Court here interpreted the Commissioner’s statements in their totality as demonstrating hostility. However, the underlying analysis by the Court could be misinterpreted to suggest that any one of the statements demonstrated that the decision-maker was not neutral; to the contrary, some of the statements taken independently do not demonstrate hostility, but rather simply state important facts, though they may be uncomfortable ones.

The Supreme Court held that the statements made by the Commissioner disparaged Phillip’s religion and compared his beliefs to the defenses of slavery and the Holocaust. It is important to first look at the commissioner’s words as two separate statements. Sentence one is, or should be recognized as, an undisputed, neutral fact. Simply stating the truth about the history of discrimination and slavery is neither biased nor hostile—in fact, it is necessary for the healing and the progress needed to ensure that we never go back to the way things were. However, simply stating historical truths about our past and weaponizing these truths by using them to denigrate a religion are distinctly different actions.

The Supreme Court had the opportunity to clarify when a statement that reckons with our country’s past is inappropriate and hostile. The Court could have done this by using the same methodology used to analyze other statements by the Commission. When the Supreme Court analyzed whether the comments that Phillips can “believe what he wants to believe” but cannot act on those beliefs “if he decides to do business in the state” demonstrated hostility, the Court provided the two possible interpretations of the comments. The first interpretation of these two statements was that they were not hostile because they merely intended to convey that Phillips could not discriminate against patrons if he wanted to do business in the state. The Court rejected this interpretation, determining that in context, these statements were not mere recitations of fact, but rather a “dismissive comment showing [the] lack of due consideration for Phillips’ free exercise rights.” The Court explained the reasons why it believed that the Commissioner’s statements more closely aligned with the latter interpretation.

However, the Supreme Court does not give the statements mentioning slavery and despicable usages of religion the same methodological treatment. Similar to the previous comments, there are two possible interpretations of the statements invoking slavery and the Holocaust. The first interpretation, the interpretation accepted by the Court, is that the statements describe Phillips’ religion as despicable and compare his religious beliefs to defenses of slavery and the Holocaust. I agree with the Court that if a Commissioner stated that Philips’ religion was despicable and compared his religion to a defense of slavery, the statements would be hostile and inappropriate. On the other hand, an alternative interpretation takes the two sentences separately and reads sentence two in light of the facts presented in sentence one to bemoan the use of religion to justify discrimination throughout history, not to disparage religion itself. Because there are two possible interpretations of the same statements, one that is acceptable and one that is not, the Court missed an opportunity to expressly state when and in what context those statements are hostile versus not hostile.

Although Masterpiece Cakeshop missed the opportunity to make these important distinctions and recognize that simply reckoning with our past is not always in and of itself hostile, the Court unequivocally endorses “the recognition that gay persons and gay couples cannot be treated as social outcasts or as inferior in dignity and worth.” For that reason, Masterpiece Cakeshop is still an important affirmation by the Supreme Court of the words printed on the outside of the building “Equal Justice Under Law.” As senators review the record of the new Supreme Court nominee to replace Justice Kennedy, it is imperative that they ensure that the nominee is committed to defending equal justice under law.

Briana Clark is a legal intern with the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. She is a rising 2L at Yale Law School and a graduate of the University of Georgia with degrees in Criminal Justice, Political Science, and Sociology.